This analysis has

been written for Iraq Petroleum 2018, which is organized by The C.W.C. Group, an energy and

infrastructure conference, exhibition and training company. This year, the

conference will take place in Berlin, Germany, on February 27-28, 2018.

February

7, 2018

LONDON — After the important military victories

obtained in the past months against the Islamic State, 2018 must be for Iraq

the year of the country’s political and economic consolidation. In May 2018, there

will be the parliamentary elections of the Council of Representatives, which

will in turn elect the Iraqi president and prime minister. At the same time, it

is quite evident that political stability is deeply intertwined with the

development of Iraq’s economy. And, if on the one hand, without strong and

unified political institutions, there won’t be credible economic development,

on the other hand, without a strong economic sector, there won’t be firm and

lasting political institutions.

Relaunching and improving Iraq’s economy cannot be

separated from supporting and expanding the development of the petroleum (oil and

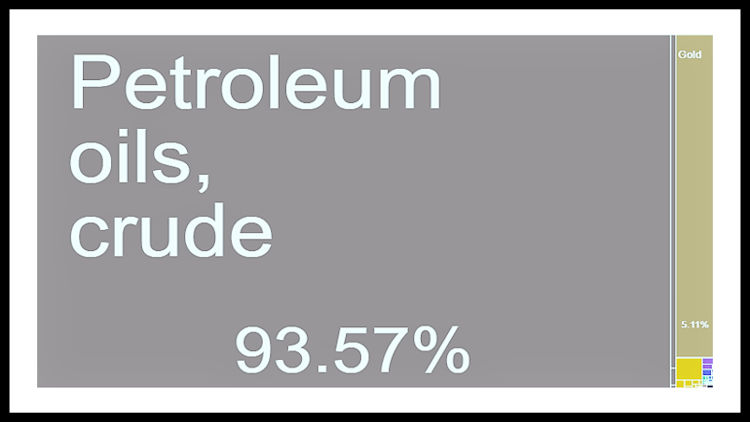

gas) industry in the country. Today, Iraq’s economy is the world’s most

dependent on oil. Approximately 58% of the country’s G.D.P. and almost 94% of

its exports are petroleum oils; oil provides more than 90% of government

revenues and 80% of foreign exchange earnings. These numbers tell that thinking

of alternative economic routes—other than the hydrocarbons route—to provide the

Iraqi government with the economic resources necessary to manage the country is

premature. Oil is Iraq’s national treasure. In January 2018, Iraq produced 4.36

million barrels of crude oil per day and exported from its southern ports 3.53

million barrels per day—Iraq’s total exports should be higher if we add 200,000

barrels per day exported by the Kurdistan Regional Government (K.R.G.) to

Ceyhan, Turkey.

|

What Did Iraq Export in 2016? — Source: The Atlas

of Complexity, Harvard University

|

Absolutely, this does not mean to rule out the

development of other economic sectors apart from the petroleum sector, but it’s

an honest assessment of what can be done and what cannot be done at this point

in time. The draft federal budget law of Iraq for 2018 confirms this point

(data of November 2017). In fact, the draft law reveals estimated revenues of

more than 85.331 trillion dinars, of which about 72 trillion dinars comes from

the oil sector. The oil revenue was calculated on the basis of $43.4 per barrel

of oil, but of course, higher oil prices mean a higher oil-sector revenue. Presently,

Iraq’s overall development must pass through the production of oil and gas.

Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi has recently stated

at the World Economic Forum, in Davos, Switzerland, that his country might need

up to $100 billion to fix its crumbling infrastructure and severely damaged

cities. The prime minister made very clear that Iraq cannot provide this amount

through its own budget, nor will donations provide it. These economic resources

must arrive in Iraq in the shape of foreign direct investment (F.D.I.).

THE

I.O.C.s’ APPROACH AS FOR INVESTING IN IRAQ

With reference to the oil and gas sector, the

international oil companies (I.O.C.s) are carrying out more than one approach

concerning whether to invest in Iraq. In general, the I.O.C.s do not share the

same vision regarding their investment presence throughout the world. Minister

of Oil Jabbar Al-Lueibi has recently called on the I.O.C.s to participate in

tenders organized by the Ministry of Oil and affirmed that Iraq is improving the

work conditions for foreign firms that want to do business in the country.

In Iraq, Anglo-Dutch Shell wants to exit its oil

investments, while U.S. Chevron wants to continue investing in the country with

the idea of possibly expanding its portfolio. In specific, Shell, with the

approval of the federal government, has very recently sold its 20% stake in the

giant oil field West Qurna 1 to Japan’s Itoche Corporation. In West Qurna 1,

the other members of the operating consortium are U.S. ExxonMobil (the

operator, 33% stake), PetroChina (25%), Iraq's state-run Oil Exploration

Company (12%) and Indonesia’s Pertamina (10%). Moreover, Shell wants to divest

of its stake in the giant oil field Majnoon as well; it’s currently planning to

hand over its stake to Basra Oil Company (B.O.C.) by the end of June 2018—the

Iraqi government is forming an executive committee to operate the field after

the withdrawal of Shell. Presently, at the Majnoon field, Shell is the operator

(45% stake), while the other members of the consortium are Malaysia’s Petronas

(30%), and Iraq's state-run Missan Oil Company (25%). In addition to Shell, also

Petronas wants to exit this investment.

Conversely, Chevron affirmed in mid-January 2018

that it intended to return to its investments in the K.R.G. with the goal of restarting

there its drilling operations, which it had stopped last fall when the tension

between the K.R.G. and Iraq proper had mounted up. At the same time, Chevron might

form a consortium with Total and PetroChina to develop the Majnoon oilfield. Moreover,

the Iraqi authorities declared last fall that China National Petroleum

Corporation (C.N.P.C.), British Petroleum, and Italy’s E.N.I. were all possibly

interested in taking over a stake in the Majnoon oil field.

After the events of last October between the

K.R.G. and Iraq proper, the presence of an additional oil major, Chevron, in both

the K.R.G. and in Iraq proper might really be a diplomatic tool capable of helping

appease the tense relationships between Erbil and Baghdad. In this regard, four

months after the reoccupation by the federal troops of the oil fields around

Kirkuk, it’s still unclear how the K.R.G. and Iraq proper will solve their

quarrel—a point of convergence between the two parties might be found on the

basis that the K.R.G. needs cash while Iraq proper wants to continue exporting crude

oil via the Kurdish pipeline.

In specific, it will be interesting to understand

whether in the whole Iraq (Iraq proper and the K.R.G.), after the political

developments of the past four months, it will be prolonged the coexistence of

two types of petroleum contracts, i.e., technical service contracts (T.S.C.s)

in Iraq proper and production sharing contracts (P.S.C.s) in the K.R.G. In

fact, since the signature of the first P.S.C. by U.K.-Turkish Genel Energy and

the K.R.G. for the Taq Taq field in July 2002 (before the fall of Saddam

Hussein, although the contract was then amended in January 2004) the federal

government has been declaring the K.R.G. P.S.C.s illegal because according to

the federal government the only authority wielding the power to sign off on petroleum

contracts for the whole Iraq is the federal government. It’s in the last ten

years that the K.R.G. has signed most of its P.S.C.s.

IRAQ AND

THE I.O.C.s WANT TO CHANGE THE PRESENT T.S.C.s

When Iraq reopened its petroleum sector to the

I.O.C.s, it chose to use T.S.C.s because they permitted Iraq to retain more

control over the reserves and produced oil and gas while maintaining full

control over the production rate and operation progress. Despite the reasons

behind this choice, it’s a matter of fact that presently neither the government

nor the I.O.C.s are happy with the T.S.C.s. So, if Iraq wants to improve the

attractiveness of its upstream petroleum sector, it has to revise the terms of

the T.S.C.s. In fact, if on the one hand, the Iraqi petroleum model contract

gives satisfactory results to the Iraqi government when oil prices are high, on

the other hand, it has a disastrous impact on the Iraqi coffers when oil prices

are low. The reason is that, despite low oil prices, the federal government

must always pay the same fees to the I.O.C.s.

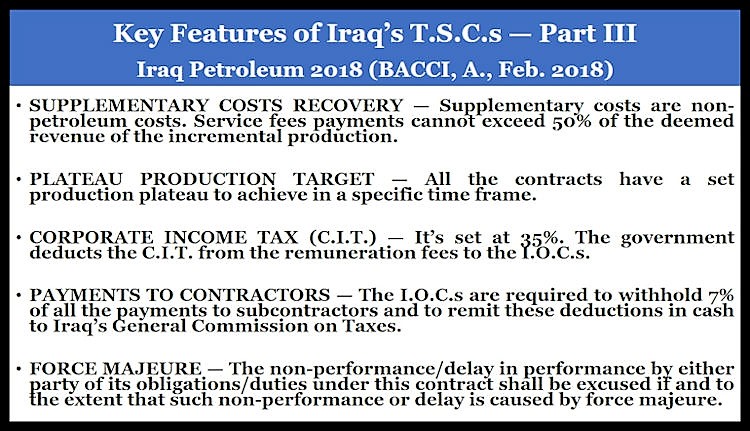

Below are the key features of Iraq’s T.S.C.s (the

following information comes from the Rumaila T.S.C.—Rumaila was an already

producing field when the federal government auctioned it off in 2009):

- Duration — The duration of T.S.C.s in Iraq is 20 years extendable to 25 years.

- License — The license is held by one of Iraq’s national oil companies (N.O.C.s). In the original T.S.C., the N.O.C.s had a 25% stake in the winning consortium, but over the years this stake in some of the T.S.C.s has been reduced.

- Signature Bonus — The I.O.C.s pay a signature bonus in cash upon the signature of a T.S.C. The initial T.S.C.s envisaged the signature bonus as recoverable, in practice, it was a soft loan that the I.O.C.s made to the government. It seems that the government of Iraq has now slashed some signature bonuses and transformed them into lower unrecoverable payments.

- Remuneration Fee — (1st bid term in the bid round) The I.O.C.s receive a fixed remuneration fee per barrel of crude oil applicable for all calendar quarters during any given calendar year. This fee is determined on the basis of an R-factor calculated at the end of the preceding calendar year for the field. The remuneration fee starts at the level that was the bid by the I.O.C.s. However, as the profitability of the operations goes up, the fees go down on the basis of a percentage scale in the contract.

- Baseline Production Rate — This is the field’s production rate before any development. The contracts assume that this baseline production rate declines at the compounded annual rate of 5%.

- Incremental Production During a Period of Time — This is the incremental volume of net production from the field during the said period that is realized in excess of the deemed net production volume at the baseline production rate.

- Petroleum Costs Recovery — The I.O.C.s receive reimbursement through service fees relating to the costs and expenditures incurred and/or the payments made by the I.O.C.s in connection with or in relation to the conduct of petroleum operations (capex and opex are included, but the corporate income taxes paid in Iraq are not included) determined in accordance with the provisions of the T.S.C.s.

- Petroleum Operations — Petroleum operations encompass all appraisal, development, redevelopment, production operations, and any other related activities.

- Supplementary Costs Recovery — Supplementary costs are non-petroleum costs, which primarily include the signature bonus (now it would probably more correct to say “included”) and de-mining costs. Service fees payments cannot exceed 50% of the deemed revenue of the incremental production.

- Plateau Production Target — (2nd bid term in the bid round) All the contracts have a set production plateau to achieve in a specific time frame.

- Corporate Income Tax (C.I.T.) — It’s set at 35%. The government deducts the 35% C.I.T. from the remuneration fees to the I.O.C.s. The income tax is received as crude oil.

- Payments to Contractors — The I.O.C.s are required to withhold 7% of all the payments to subcontractors and to remit these deductions in cash to Iraq’s General Commission on Taxes.

- Force Majeure — The non-performance or delay in performance by either party of its obligations or duties under this contract shall be excused if and to the extent that such non-performance or delay is caused by force majeure.

According to the T.S.C.s, the payments from the

federal government to the I.O.C.s are based on production levels and not on the

specific project revenue—it’s always a fixed amount for every barrel of crude

oil produced. So, with low oil prices, the government earns necessarily less.

In September 2016, Platts, one source of benchmark price assessment in the

physical energy market, estimated that the

proportion of oil revenues paid in cost recovery and remuneration fees was

around 16% when oil prices were above $100 per barrel, but that it rose to as

high as 48% with significantly lower crude oil prices.

And, to add insult to injury, as per their

contract, until they reach the established production plateau, the I.O.C.s must

increase their crude oil production. And the more barrels are produced, the

more fees the federal government must pay to the I.O.C.s despite low oil

prices. In general, this payment is done in kind, which means that, with low

oil prices, the federal government needs a greater volume of crude oil to pay

the I.O.C.s.

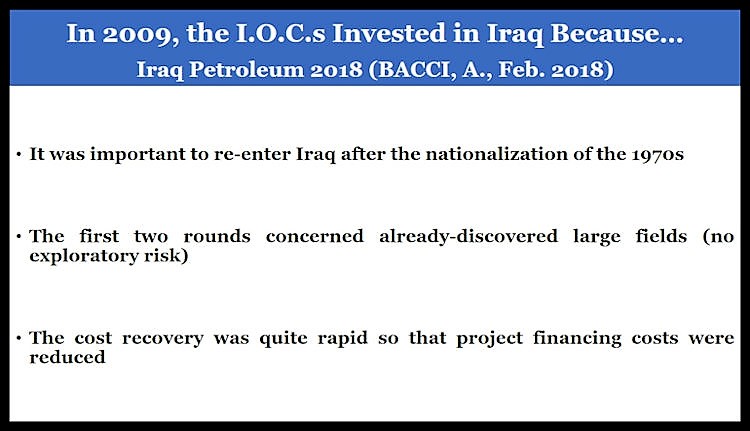

At the same time, the I.O.C.s have never been

particularly fond of the T.S.C.s because the reimbursement fee was quite low

for production after a certain threshold and because there were important

upfront costs they had to sustain. In any case, at the time of their signature,

the I.O.C.s decided to invest in Iraq because

- it was important to re-enter Iraq after the nationalization of the 1970s

- the first two rounds concerned already-discovered large fields (no exploratory risk)

- the cost recovery was quite rapid so that project financing costs were reduced

However, also for the I.O.C.s. there is something

more. With low oil prices, the T.S.C.s prescribe that the I.O.C.s’ remuneration

should remain the same, but if the federal government is not able to pay, it

will postpone its payments, i.e., the I.O.C.s will have increased financing

costs. In addition, cost recovery is capped to a percentage of “deemed value,”

which is “net production” in a quarter multiplied by the “provisional export

oil price” for that quarter. This means that with low oil prices, there could

be a decrease in the amount received by the I.O.C.s. as well.

Additionally, on the one hand, the I.O.C.s

complain consistently about procurement procedures in Iraq. In fact, the

applied lowest price principle initially reduces the costs, but later it increases

them because the subcontractors to obtain their contracts propose low bids,

which are impossible to carry out in the future if not with additional

expenditures. However, on the other hand, because Iraq obtains 100% of the

revenue after cost recovery and remuneration fee, the I.O.C.s get more profit

if the costs are higher. In the end, there is no real incentive for the I.O.C.s

to be cost efficient; what is missing is a way for the I.O.C.s to work in a

more efficient and cost-effective manner.

Summing up, independently of what investment

strategy the I.O.C.s want to carry out in Iraq, the sure recipe for the Iraqi

government to getting a better profitability for itself from the country’s

petroleum sector is to improve the terms of its T.S.C.s. At the same time, with

the present oil prices, improved fiscal terms are of paramount importance also to

attract the I.O.C.s. This logic holds true for both oil and gas fields on offer

through licensing rounds and for oil and gas fields on offer through direct

negotiations.

THE PAST

FOUR BID ROUNDS AND THE “PROJECT”

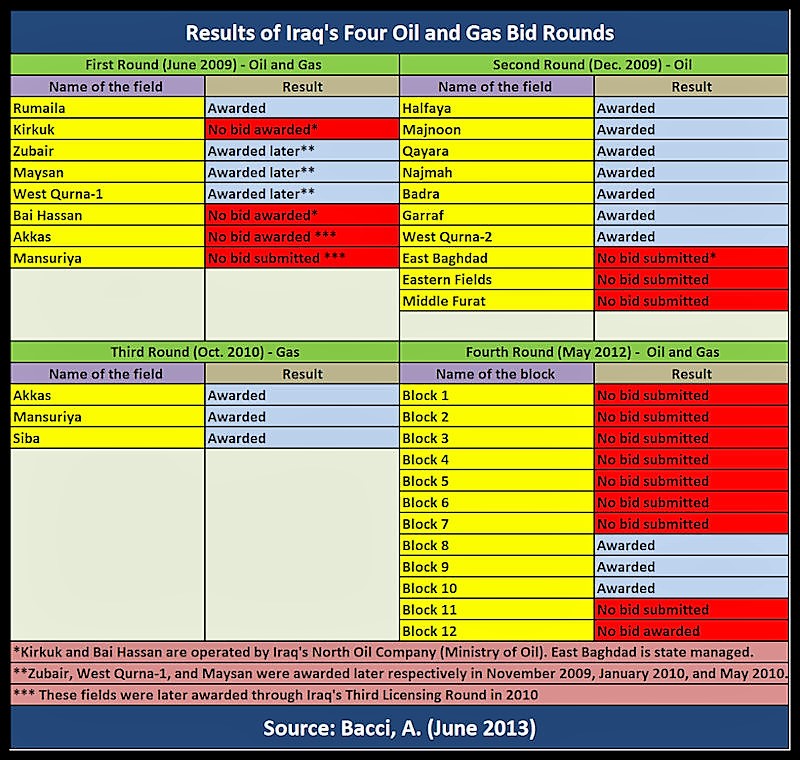

Until now, Iraq has organized four bid rounds

since 2009:

- First Round (June 2009) — This round included the supergiant oil fields Rumaila, Zubair, and West Qurna 1, which had been until then under the operatorship of Iraq’s South Oil Company (S.O.C., today known as Basra Oil Company, B.O.C.). In total, eight fields were on offer. Companies were bidding on two parameters: remuneration fee and plateau production target. Initially, this bid round auctioned off successfully only the Rumaila oil field to BP for a remuneration fee of $2, but, on the bidding day, BP did not sign any contract and all the other seven auctioned fields were not assigned. Only after some months, did BP sign its contract for Rumaila. However, it was a modified version of the contract because, while the remuneration fee stayed the same, the cost recovery was quicker so that project financing costs were reduced giving the company an improved net present value (N.P.V.)—according to BP, after the amendments, the return on the investment was about 20%. Thanks to the improved terms, after the Rumaila signature, Iraq signed contracts also for Zubair, West Qurna 1, and Maysan (oil).

- Second Round (December 2009) — In this second bid round, Iraq awarded seven oil fields: Majnoon, West Qurna 2, Halfaya, Garraf, Badra, Qaiyarah, and Najmeh. The three other fields on offer did not receive any bids; companies were probably worried by the security conditions on the fields or they could not see an interesting profitability in signing T.S.C.s for those fields.

- Third Round (October 2010) — Iraq had not been able to sign off on a single gas contract with its first two bid rounds, so the country organized a round where there were on offer only three gas fields: Akkas, Siba, and Mansuriya. In fact, developing dedicated gas production for supplying domestic power plants and the petrochemical industry was preferred to using associated gas obtained from the oil fields. Few small companies showed up the day of the bid round, but all the three gas fields were awarded.

- Fourth Round (May 2012) — The fourth round pertained to auctioning 12 blocks (called block 1, 2, 3, and so on) scattered throughout the country with the goal of exploring for oil. In other words, we are not talking of rehabilitating or increasing the production of already producing fields but of exploring for oil. This bid was unsuccessful for Iraq because only three blocks (blocks 8,9, and 10) were awarded. The reason for the failure was that the terms were not guaranteeing the oil companies sufficient profits.

So, in the end, despite some difficulties, especially

for the first bid round, the first three bid rounds have been successful for

Iraq. Instead, the fourth one has not provided Iraq with a positive outcome. In

any case, it was with the three first rounds that Iraq literally opened its oil

and gas sector to the I.O.C.s. It’s important to underline that, if the

companies had been able to meet their contract targets, the eleven oil contracts

signed with the first two bid rounds would have increased the country’s oil

production by about 11.7 million barrels by 2018.

The four bid rounds show the importance of finding

a balance between the government’s interests and the companies’ interests.

However, at the same time, licensing rounds are a very good tool for finding

out how a government and the interested companies view the assets on offer.

Many a time, value evaluation of the assets may be completely different. For

example, in Iraq, in the first licensing round, with reference to the Bai

Hassan field, there was a significant difference between the remuneration fee

offered by a consortium formed by U.S. ConocoPhillips, and two Chinese

companies, China National Offshore Oil Corporation (Cnooc) and Sinopec. The

companies requested a remuneration fee of $26.70, but the maximum remuneration

fee that Iraq was available to pay was $4.00. As a result, Iraq did not award

Bai Hassan.

Over the course of the years since the signature

of the contracts, Iraq has already revised twice the country’s production

target. At the time of the four bid rounds, Iraq had envisaged to reach 12

million barrels per day of oil output capacity by 2018. Now, the general goal,

revised the last time in 2015, is to have a production of 5.6 million to 6

million barrels per day by 2020. A first revision occurred in 2014 when the

production target was moved to about 8.4. million to 9.0 million barrels per

day by 2020. In this regard, the plateau revisions in Rumaila’s contract are

quite emblematic. When the contract was signed in 2009, the plateau was set at

2.85 million barrels per day. Then, in 2014, the plateau was reduced to 2.1

million barrels per day by 2020. Finally, in October 2017, it emerged that BP

was again in discussions with the Ministry of Oil over the output levels at

Rumaila, which is currently producing 1.5 million barrels per day. At Rumaila,

the additional problem is that the main reservoir declines at a rate of 17%

every year so that BP needs to add 250,000 barrels per day every year to just

maintain the present production level. Apart from Rumaila’s T.S.C., some other

contracts have been amended since signature, but the nature of the amendments

has not been made public.

The idea of organizing a fifth licensing round

with improved fiscal terms for the I.O.C.s was on the radar of the Ministry of

Oil already in the summer of 2012. However, after five years and half, this

fifth licensing round or direct negotiations between the Ministry of Oil and

the I.O.C.s with no auction have still to materialize. Over this period, the

Ministry of Oil has announced at least three times its intention to put on

offer some additional oil and gas fields. The most recent line of action dates

to July 2017 when the Ministry of Oil announced the launch of a new project

(it’s called the “Project”) to explore, develop, and produce nine onshore and

offshore exploration blocks in south and middle Iraq near the borders with Iran

and Kuwait. Also in this case, according to the Ministry of Oil, there is the

willingness to modify the fiscal terms with the collaboration of the I.O.C.s as

well. The official timetable calls for the submission of bids and awards at the

end of June 2018.

Five out of the nine blocks included in this

project are in Basra Governorate. They are the three blocks Khudher Al-Mai,

Jebel Sanam, and Al Fao on the Kuwaiti border, the Sindibad block (including

the Sindibad oilfield, which is jointly owned by Iraq and Iran, and which could

have 3 billion barrels of recoverable oil) along the Iraqi-Iranian borderline,

and the Arabian Gulf block in the Arabian Gulf. The other four blocks are in

four different governorates, all on the Iraqi border with Iran. The Naft Khana

block is in Diyala Governorate, the Zurbatiya block is in Wasit Governorate,

the Shihabi block straddles between Wasit Governorate and Missan Governorate,

and the Huwaiza block is in Missan Governorate.

RECOMMENDATIONS

FOR IMPROVING THE FISCAL TERMS

When we analyze Iraq’s oil sector, one point is

quite clear: in comparison to other OPEC members, Iraq’s reserves/production

ratio has always been quite high—at the beginning of 2017, Iraq’s Ministry of

Oil declared that the country’s proven reserves had increased to 153 billion

barrels from a previous estimate of 143 billion barrels. This means that, on a

proportional basis, Iraq has always had a production lower than that of many other

OPEC members. So, logic would require that Iraq increase its oil production, if

the country wants to fully benefit from its oil endowment. And, to obtain this

target, it is important to improve the fiscal terms of the current and the

future oil and gas contracts so that both the government and the I.O.C.s might

obtain a higher profitability.

Rather than completely change the terms of the

T.S.C.s, it appears now that the federal government intends to make some

adjustments to the current contractual framework—incentivizing cost control

will be a priority, but it seems that the Ministry of Oil is thinking of

reducing the cap on the amount of admissible cost recovery and remuneration to

a fixed dollar amount.

In specific, the T.S.C.s’ revised fiscal terms

will have to address these two main points:

- Lack of Cost Efficiency — There is no alignment between the government and the I.O.C.s on obtaining the lowest costs per barrel. So, if the I.O.C.s have higher costs, they will have more oil costs to recover the incurred costs, and consequently their remuneration per barrel will be higher. In practice, this means that the I.O.C.s will obtain higher net revenues when costs are higher; no cost efficiency from the side of the I.O.C.s.

- The I.O.C.s’ Income Is Not Sensitive to the Price of Oil — The remuneration fee depends on an R-factor (the ratio of cumulative cash receipts to cumulative expenditures in the conduct of the petroleum operations), but it’s fixed according to the envisaged thresholds, so the remuneration fee is delinked from the oil price. In practice, the Iraqi T.S.C.s are attractive to the I.O.C.s with low oil prices because they have a guaranteed fee per barrel (and the companies will obtain more in-kind barrels from the government to pay the remuneration fee when oil prices are low). Instead, the Iraqi T.S.C.s are relatively unattractive to the I.O.C.s with high oil prices because the remuneration fee is fixed (in this case, the added profitability goes all to the government; plus, the I.O.C.s reduce investments exactly when the government would like to expand production).

There is

an enormous variety in the way governments and the I.O.C.s may structure their

petroleum contracts, but every one of the arrangements has different pros and

cons. Today, throughout the world there is no specific fiscal system getting

more ground, although we are witnessing some new fiscal solutions. The starting

point of all the petroleum contracts is that the more attractive the resource

base is, the tougher will be the fiscal terms. However, the beginning of the

exploitation of unconventional oil and gas resources since 2009 has brought

about a reduction in government take. On a global scale, old service contracts

show a poor alignment of governments’ goals with I.O.C.s.’ goals.

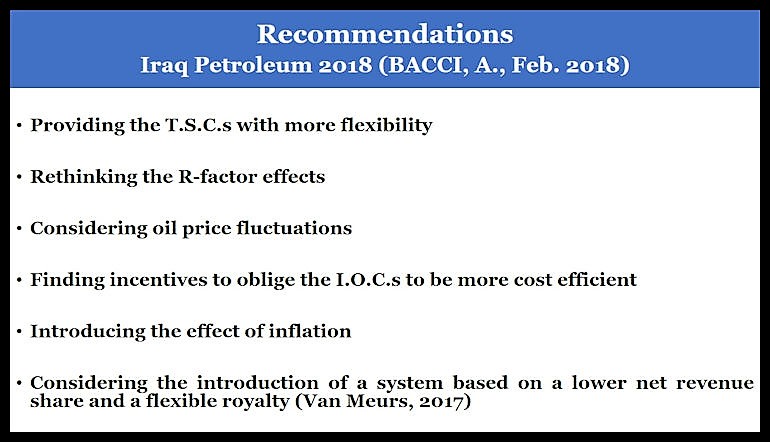

The main general

recommendations (general because more research is needed to produce a

step-by-step plan of action) to develop T.S.C.s with improved fiscal terms are

- Providing the T.S.C.s With More Flexibility – Indeed, the signed T.S.C.s have the same structure, but, in the end, they vary considerably along a variety of dimensions, such as, scope of the agreement, remuneration fee, plateau, other terms of the contract, assumptions about international markets prices, and so on. Unless the model T.S.C. is more flexible in accommodating all these different parameters, it is difficult to continue with a single model. The present T.S.C.s are probably too simple.

- Rethinking the R-Factor Effects — Under the present T.S.C.s, if the I.O.C.s incur an additional expenditure, this expenditure will result in lowering the R-factor (in fact, an additional cost increases the value of the denominator in the R-factor ratio) in addition to the reduction in government income because of the reduction in the net revenue share. And, of course, a reduction in the R-factor will increase the losses for the government.

- Considering Oil Price Fluctuations — The present T.S.C.s do not consider oil price fluctuations; remuneration fees are fixed even if oil prices experience a dropdown of more than 50%. Under high oil prices, the present T.S.C.s are unattractive to the I.O.C.s while under low oil prices they are attractive.

- Finding incentives to Oblige the I.O.C.s to Be More Cost Efficient — According to the present T.S.C.s, if the I.O.C.s have higher costs they will recover more petroleum costs (in other words, the per barrel remuneration will be higher). Right now, for the I.O.C.s there is an incentive to spend more.

- Introducing the Effect of Inflation — The present T.S.C.s are not adjusted for inflation. So, if during the 20-year term of the T.S.C.s, significant inflation happens in the United States, the value of the per-barrel fee in real terms would quickly decline.

- Considering the Introduction of a System Based on a Lower Net Revenue Share and a Flexible Royalty (Van Meurs, 2017) — In order to encourage efficient operations, the net revenue sharing rate should not exceed 60% to the government. The flexible royalty might be based on three different royalties: one royalty rate based on the daily field production, adjusted also for oil gravity and well depth; one royalty rate based on the oil price at the delivery point; and one royalty rate based on well productivity. This system could permit good returns at the same time to both the government and the I.O.C.s under different oil-price scenarios and provide strong incentives for the I.O.C.s to reduce costs.

|

Flexible Royalty Formula — Source: Pedro van

Meurs, “What Suggestions for an Iraq Single Fiscal Model for Upstream Petroleum,”

April 2017

|

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.